Ghana and the Netherlands - Historical Notes

Blog accompanying the Gold Coast DataBase with historical, biographical, and genealogical information on the relationship between Ghana and the Netherlands, from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century.

Tuesday, 20 August 2024

Variations of African Life in the Eighteenth-Century Netherlands: Between a Boy Servant at the Court of Orange-Nassau and a Lord of the Manor in the Province of Groningen

Thursday, 8 October 2020

Jacob de Petersen (1703-1780): Slave trader, West India Company official, and member of the Amsterdam city government

This blog reproduces a short biographical sketch of Jacob de Petersen (1703-1780), one of the most powerful men in the Dutch West India Company in the later 18th century. He was involved in the Atlantic slave trade for fifty-five years, both institutionally and privately. At the same time he was closely connected to the Court of the Prince of Orange Nassau at the Hague, and the top echelons of the Amsterdam city government, in which he took an active part himself.

This is the author's version of a paper published in a book on slavery and the slave trade, commissioned by the city government of Amsterdam. The article is in Dutch (as is the book). I am currently working on a publication on the subject in English.

Reference:

Michel Doortmont, 'Jacob de Petersen, slavenhandelaar op West-Afrika en Amsterdams bestuurder,' in: Pepijn Brandon, Guno Jones, Nancy Jouwe, Matthias van Rossum (red.), De slavernij in Oost en West: Het Amsterdam onderzoek (Amsterdam, Unieboek Het Spectrum, 2020), p. 104-111.

[p. 104]

Jacob de Petersen, slavenhandelaar op West-Afrika en Amsterdams bestuurder

Michel Doortmont

Als een van de constituerende Kamers van de WIC speelde Amsterdam een sleutelrol in de activiteiten van die handelscompagnie, inclusief de slavenhandel vanuit West-Afrika naar Amerika. Om de rol van Amsterdam beter te begrijpen kan het voorbeeld gebruikt worden van Jacob Baron de Petersen (1703-1780), die tussen 1725 en 1780 carrière maakte als WIC-ambtenaar, slavenhandelaar en stadsbestuurder. Een carrière die mogelijk gemaakt werd door leden van het Amsterdamse regentenpatriciaat en die datzelfde patriciaat ook ten dienste stond in de slavenhandel.

Hoewel geen Amsterdammer van geboorte, was De Petersen nauw gelieerd aan het Amsterdamse regentenpatriciaat. Zakelijke en familierelaties gingen terug tot in de zeventiende eeuw. Jacobs grootmoeder was Catharina Bicker (1642-1678), kleindochter van zowel een Amsterdamse burgemeester als een lid van de Vroedschap. De Bicker-clan had belangen in het Amsterdamse stadsbestuur, maar ook in handel en industrie op wereldschaal, inclusief Scandinavië (mijnbouw, metaalindustrie), Azië (bestuur en handel van de VOC), en West-Indië (slavenhandel, plantages, suiker- en koffiehandel). (1) Na de dood van hun moeder in 1712 en de opsluiting van hun vader vanwege psychische problemen werden Jacob en zijn broer en zusters opgevangen door de familie Bicker. Hij ging rechten studeren in Utrecht en promoveerde hier in 1725. Direct daarna volgde een benoeming tot juridisch en bestuurlijk ambtenaar bij de WIC op het eiland Curaçao. Daar zou hij tot 1739 blijven.

[p. 105]

Slavenhandelaar op Curaçao

Op Curaçao dreef De Petersen samen met de gouverneur, Juan Pedro van Collen, handel in slaven uit West-Afrika en verwierf hij een eigen plantage, Groot Sint Joris. Die handel in slaven was illegaal, want werknemers van de WIC mochten officieel niet voor eigen rekening handelen. Nu deden wel meer WIC-ambtenaren dit, maar de bedrijfsmatige wijze waarop Van Collen en De Petersen te werk gingen lijkt uitzonderlijk. (2)

Van Collen was lid van een Amsterdamse regentenfamilie die al vanaf het begin van de achttiende eeuw banden had met de WIC en de slavenhandel op Curaçao. De alliantie met Van Collen maakte van De Petersen al op jonge leeftijd een machtig en invloedrijk man. Hoe machtig bleek pas goed toen Van Collen in 1738 overleed. De Petersen had gehoopt hem als gouverneur op te kunnen volgen. Dat gebeurde echter niet, vanwege politieke perikelen in Nederland en op Curaçao. De door de Heren Tien, het hoofdbestuur van de WIC, benoemde Jan Gales keerde zich direct na aankomst op Curaçao tegen de Van Collen-gezinde Raad en andere koop-lieden, onder wie De Petersen. De situatie liep volledig uit de hand en De Petersen vluchtte uiteindelijk in 1739 naar Nederland. Die actie stond gelijk aan desertie en zou het einde van zijn WIC-carrière betekend moeten hebben.

[p. 106]

Een bestuurlijke doorstart

Na terugkeer in Nederland werd De Petersen verhoord door de bewindhebbers van de Kamer Amsterdam. Hij bepleitte zijn zaak met succes en hij werd in zijn functie hersteld. Gouverneur Jan Gales werd ontslagen. Eén van de gronden voor het ontslag was dat Gales zich met particuliere handel had ingelaten, precies hetzelfde waaraan De Petersen zich ook schuldig had gemaakt. Het is duidelijk dat hij betere contacten en beschermheren in Amsterdam had. Terug naar Curaçao ging hij niet. In plaats daarvan werd De Petersen op 23 augustus 1740 benoemd tot directeur-generaal (gouverneur) in West-Afrika. De benoeming betekende enerzijds eerherstel, maar anderzijds ook een functie met mogelijkheden rijk te worden in de slavenhandel. (3) Om te begrijpen wat dit voor De Petersen betekend moet hebben toen hij de benoeming aanvaardde moeten we kijken naar de ontwikkelingen in het apparaat van de WIC in deze periode.

In 1674 werd de tweede WIC opgericht als doorstart van haar failliete voorganger. De belangrijkste activiteit van de nieuwe organisatie was de handel in goud, ivoor en slaven. Aan de Afrikaanse zijde van de handelsdriehoek Europa-West-Afrika-Caribisch gebied was het in 1637 op de Portugezen veroverde St. George d’Elmina het administratieve hart van de Nederlandse slavenhandel. Alleen bleek allengs dat de (slaven)handel onder monopolie door de WIC niet winstgevend genoeg was. Daarom werd vanaf 1730 dit monopolie in verschillende stadia afgeschaft: eerst voor alle gebieden in Afrika buiten de Goudkust, daarna ook voor de Goudkust zelf. Dit betekende dat particulieren zich op de handel in slaven mochten toeleggen, tegen betaling van zogenaamde recognitie, een belasting per ingekochte slaaf.

Al voordat de WIC vanaf 1730 haar monopolie op de (slaven)handel op-gaf, was er een stevige competitie tussen de twee belangrijkste Kamers Amsterdam en Zeeland van de WIC over de bezetting van de post van directeur-generaal over de Goudkust. Die werd in de periode van private handel alleen maar sterker. De Kamer die Elmina en daarmee de Goudkust in handen had kon immers bepalen wie bevoordeeld werd in de handel. (4)

[p. 107]

De periode tussen 1730 en 1740 verliep voor de WIC in West-Afrika tamelijk chaotisch. Alle betrokkenen moesten wennen aan de nieuwe omstandigheden. Tussen 1730 en 1734 was het de Amsterdamse Jan Pranger (1700-1773) die de transitie begeleidde. Zijn bewind werd echter gemarkeerd door het verlies van de belangrijke handelsrelatie met het naburige koninkrijk Dahomey en leidde tot zijn ontslagverzoek. (5) Zijn directe opvolgers ging het ook niet voor de wind. Met name directeur-generaal M.F. de Bordes, in dienst van de Kamer Zeeland, was een ramp. De man joeg niet alleen al zijn ambtenaren tegen zich in het harnas, maar ontketende bovendien bijna een oorlog met de lokale bevolking. Toen berichten over het disfunctioneren van De Bordes Nederland bereikten, grepen de Heren Tien direct in en benoemden De Petersen als opvolger. Diens lange staat van dienst en de politieke noodzaak hem aan een nieuwe betrekking te helpen, zullen daarbij een rol hebben gespeeld. Voor de Kamer Amsterdam was het een gelegenheid de macht in Afrika opnieuw – na het vertrek van Jan Pranger – naar zich toe te trekken middels de aanwezigheid van een lid van het patriciaat, een insider.

Slavenhandelaar op de Goudkust

Jacob de Petersen had ook zijn eigen motieven om de functie te aanvaarden. Voor hem was het een uitdaging om de chaotische bestuurlijke toestand op de Goudkust te corrigeren en zijn naam als succesvol WIC-bestuurder te bevestigen. Er waren ook economische perspectieven. Aanvankelijk was het onder het nieuwe vrijhandelsregime aan WIC-ambtenaren toegestaan particuliere handel te drijven en kon men als agent voor particuliere slaven-handelsfirma’s optreden. Wat in Curaçao nog in het geheim moest, kon De Petersen nu dus in alle openheid doen. Hoewel hierover geen eenduidige gegevens beschikbaar zijn – het wachten is op een goede studie op basis van het nader ontsloten Amsterdamse notarieel archief – mogen we aannemen dat het kapitaal voor deze particuliere slavenhandel van de Amsterdamse familie- en vriendenrelaties in het regentenpatriciaat afkomstig was.

De Petersen bleef van 1741 tot 1747 in Elmina. Tijdens zijn bewind werd de transitie naar vrije handel voltooid en bouwde hij het lokale WIC-apparaat opnieuw op. Hij sloot daartoe allianties met verschillende WIC-ambtenaren die hij op strategische posities neerzette, waardoor het lokale netwerk van kooplieden-ambtenaren voor de organisatie van de slaven-handel versterkt werd. Onderdeel van deze strategie waren ook allianties met lokale Afrikaanse kooplieden, zodat de aanvoer van slaven uit het binnenland naar de kust gegarandeerd werd. (6)

Met ingang van 1746 verbood de WIC de particuliere handel aan haar medewerkers. Het beleid zwalkte hier nogal. Voor De Petersen was dit reden om al op 1 juli 1745 zijn ontslag in te dienen. Vermoedelijk viel de Goudkust hem ook tegen. Er bleven problemen met het personeel. En belangrijker nog: door politieke conflicten in het binnenland liep de handel sterk terug. Het duurde bijna twee jaar voordat hij daadwerkelijk vertrok. In april 1747 ging hij scheep naar Suriname op het particuliere schip Watervliet. Aan boord waren ook 400 slaven, bestemd voor de verkoop in Suriname. Het schip arriveerde in juli 1747 in Paramaribo, maar toen waren er nog slecht 150 slaven aan boord. De rest zou onderweg gestorven zijn ‘door een langdurige en bedroefte reise’. (7)

Amsterdamse regenten in de slavenhandel

De Watervliet maakte tussen 1743 en 1747 drie reizen met slaven van West-Afrika naar Curaçao en Suriname. (8) Van de eerste reis is bekend dat de investeerders uit het Amsterdamse regentenpatriciaat afkomstig waren, inclusief [p. 109] erschillende zittende bestuurders. Zo investeerden de Vroedschapsleden Jan Bernd Bicker, Gerard Bors van Waveren, Pieter Clifford, Gerrit Hooft Gz., Harman Henrik van de Poll, Pieter Rendorp en Jonas Witsen in de reis. Bicker, Clifford, Hooft en Van de Poll waren op enig moment ook bewindhebber van de WIC en Bicker en Van de Poll ook directeur van de Sociëteit van Suriname. (9)

De Petersen wordt niet genoemd als investeerder, maar aangenomen mag worden dat hij mede-initiatiefnemer was voor meerdere slavenreizen. De latere financiële positie van De Petersen bevestigt dat hij een zeer vermogend man was. Een dispuut over een zending goud uit Suriname ter waarde van ruim 111.000 gulden, die op zee gestolen zou zijn door kapers, bevestigt dit al, maar ook de levensstijl die hij er in Nederland op na hield en het aantal personen dat hij onderhield wijzen hierop. De oorsprong van deze rijkdom kan alleen maar gevonden worden in winsten uit de slavenhandel. (10)

Na zijn terugkeer in Nederland vestigde Jacob de Petersen zich in Am-sterdam, waar hij in 1750 een monumentaal huis kocht op de Keizersgracht, voor een bedrag van 55.600 gulden dat hij contant betaalde. Hij bezat verder nog een huis en tuin in de Plantage, ‘daar het Moortje boven de deur staat,’ een duidelijke verwijzing naar zijn Afrikaanse en slavenhandelsbetrekkingen. In 1766 kocht hij een tweede pand aan de Keizersgracht.

WIC-bestuurder in Amsterdam

Ondanks zijn rijkdom ging De Petersen niet rentenieren. Hij was bij terugkeer uit Afrika ook pas vierenveertig jaar oud. Hij bleef bestuurlijk actief en zette zijn WIC-carrière in Amsterdam voort. Al in 1748 werd hij op voordracht van de burgemeesters bewindhebber in de Kamer Amsterdam. In die hoedanigheid bekleedde hij vele malen de functie van president-bewindhebber, onder andere bij de installatie van Erfstadhouder Prins Willem V als opperbewindhebber en gouverneur-generaal van de WIC in 1768. Van die gebeurtenis is door de kunstenaar Fokke Simons een prent vervaardigd waarop De Petersen ook afgebeeld is. Met de benoeming van Prins Willem V als opperbewindhebber werd er ook een verte-genwoordiger van de prins benoemd. Vanaf 1766 was dit Mr. Ferdinand van Collen (1708-1789), raadsman in de Vroedschap en oud-commissaris en oud-schepen van Amsterdam. Van Collen was een neef van De Peter-sens oude compagnon op Curaçao, gouverneur Juan Pedro van Collen. Jacob de Petersen nam in 1770 het stokje over en werd daarmee tot zijn dood in 1780 de machtigste man in de WIC. Daarnaast bekleedde hij een reeks andere bestuursfuncties, waaronder die van schepen van Amsterdam en directeur van de Sociëteit van Suriname. (11)

[p. 110]

|

| prent door Fokke Simons; 1771; Rijksmuseum Zittingneming van Willem V tussen de directeuren van de WIC bij zijn bezoek aan Amsterdam in 1768. |

In zijn nieuwe leven in Amsterdam veronachtzaamde De Petersen zijn Afrikaanse contacten niet. Hij bleef zijn beschermelingen ondersteunen. Daarmee zorgde hij er ook voor dat de Amsterdamse belangen in West-Afrika vertegenwoordigd bleven. Na verloop van tijd werd privéslavenhandel voor WIC-ambtenaren in West-Afrika opnieuw toegestaan. Dat leidde tot een hausse aan particuliere activiteiten onder deze ambtenaren, in samenwerking met leden van het Amsterdamse regentenpatriciaat. De Petersen sloeg ook een brug tussen datzelfde patriciaat en leden van de Amsterdamse middenklasse, gegoede burgers zonder directe relatie tot het bestuur. Jan Pranger, zijn voorganger als Amsterdamse directeur-generaal op de Goudkust en zoon van een Amsterdamse wijnhandelaar, is daar een voorbeeld van. Met hem onderhield hij een jarenlange persoonlijke en zakelijke vriendschap en beheerde hij diverse belangen in de Afrikaanse slavenhandel. Twee van zijn beschermelingen, de Amsterdamse Nicolaas Mattheus van der Noot de Geeter en de Duits-Groningse Pieter Woortman volgden hem zelfs – dankzij zijn steun – op als directeur-generaal in Elmina.

[p. 111]

In Amsterdam was De Petersens huis een verzamelpunt voor Afrika- en West-Indiëgangers, inclusief kinderen uit gemengde Europees-Afrikaanse relaties. Ook waren er verschillende Afrikaanse bedienden te vinden. (12)

Jacob de Petersen was een spil in het web van de Atlantische slavenhandel in West-Afrika in een periode dat deze grote veranderingen onderging. Als zodanig was hij, met zijn eerstehands ervaring in de handel in Curaçao en op de Goudkust, zijn zakelijk en bestuurlijk inzicht en zijn solide betrekkingen met het Amsterdamse regentenpatriciaat, een bijzonder voorbeeld van de manier waarop het burgerlijk bestuur van Amsterdam in formele en informele zin direct betrokken was bij de slavenhandel in West-Afrika.

Notes

- M.R. Doortmont, ‘Van kamerheer tot binnenmoeder: De Rijksbaronnen De Petersen in de Nederlanden, 1650-1914,’ De Nederlandsche Leeuw: Tijdschrift van het Koninklijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Geslacht- en Wapenkunde 116 (1999), kol. 97-174, 278-314, 482, aldaar kol. 119-120.

- Ibidem, kol. 136-143, 282-284.

- Ibidem.

- H. den Heijer, De geschiedenis van de WIC (Zutphen 1994) 163.

- H. den Heijer, Goud, ivoor en slaven: Scheepvaart en handel van de Tweede Westindische Compagnie op Afrika, 1674-1740 (Zutphen 1997) 325-335.

- De rol van Afrikaanse kooplieden en politieke machthebbers in de Atlantische slavenhandel is sinds de Jaren 1970 onderwerp van internationale academische discussie. Hoewel een belangrijk debat, is er hier geen ruimte verder op die rol in te gaan. Volstaan moet worden met te constateren dat er in de organisatie van de slavenhandel in West-Afrika handelsnetwerken ontston-den waarin Afrikaanse en Europese kooplieden nauw samenwerkten, ieder met hun eigen belangen. Zie voor Nederlandse betrekkingen o.a. M.R. Doortmont, ‘An overview of Dutch relations with the Gold Coast in the light of David van Nyendael’s mission to Ashanti in 1701-1702,’ in: I. van Kessel (red.), Merchants, Missionaries & Migrants: 300 Years of Dutch-Ghanaian Relations (Amsterdam 2002), 19-32; M.R. Doortmont, ‘The Dutch Atlantic Slave Trade as Family Business: The case of the Van der Noot de Gietere – Van Ba-kergem family,’ in: J.K. Anquandah, N.J. Opoku-Agyemang en M.R. Doortmont (red.), The Transatlantic Slave Trade: Landmarks, Legacies, Expectations (Accra 2007), 92-137; H. den Heijer, De geschiedenis van de WIC, 151, 163-174, 177-179, passim; H. den Heijer, Goud, ivoor en slaven, 89-166, 220-262, 297-373.

- Nationaal Archief Suriname, Oud Archief Suriname, 1.05.10.01, inv.nr. 4, Journaal 1744-1748, inschrijving maandag 17 juli 1747, scan 322.

- Voor de drie reizen van de Watervliet en verdere details zie de website ‘Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade – Database’ en de daar genoemde literatuur en bronnen.

- Voor de lijst van investeerders zie Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Notarieel Archief Amsterdam, 5075, inv.nr. 2837, akte 26 november 1745, averijgrosse schip Watervliet. Persoonsgegevens ontleend aan J.E. Elias, De Vroedschap van Am-sterdam, 1578-1795 (Amsterdam 1903-1905).

- Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Notarieel Archief Amsterdam, 5075, inv.nr. 10243, akte 10 januari 1748, scheepsverklaring.

- M.R. Doortmont, ‘Van kamerheer tot binnenmoeder,’ kol. 136-143, 282-284.

- Vergelijk Ibidem; N. Everts, ‘Cherchez la Femme: Gender-Related Issues in Eighteenth-Century Elmina,’ Itinerario 20 (1996) 45-57.

Sunday, 21 August 2016

An African baptism in Delft, 1794

"Baptism of a negro lady from the Coast of Africa"

In the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, there is an image of a baptism ceremony of a 'negro lady from the Coast of Africa.' The caption further reads that the ceremony took place in the Remonstrant Reformed church of Delft on 24 September 1794. In pen is added that the ceremony was performed by the Rev. Pieter van der Meersch, and that the the ceremony was set to Ephesians 5 verse 8: "For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Live as children of light." On the pulpit a reference is made to Psalm 36, but it is unclear if this has bearing on the ceremony.The image is detailed, with the African lady kneeling, the minister performing the baptism and a man and a woman assisting. A considerable congregation is looking on. However, except for the name of the minister, nobody is mentioned by name. Apparently the maker of the print and caption was more interested in the rarity value of the occasion - an African lady being baptised - than in the human aspect of it, in terms of a social occasion.

As the date and location of the baptism are mentioned in the caption, it is possible to look up the original registration of in the records of the Remonstrant Reformed Church of Delft. As it happens these have been digitised and can be found here.

"An African young daughter [...] named Maria Zara Johanna"

The registration is very elaborate and runs as follows:"The 24th of September on Wednesday night was baptised in this church, by Rev. A. van der Meersch, an African young daughter, who was named at Holy Baptism Maria Zara Johanna. As witnesses stood the overseer Johannes Guus, and Ms. Zara Turfkloot, wife of Rev. Van der Meersch, who also led her to Holy Baptism. According to her own information she was born in Zoogwoin, on the Coast of Guinea, a day's travel from St. Elmina [sic], and probably circa 24 years old. Her father's name is Cajo Sainquo Niabi, and her mother's name is Masa Oribo. She was repatriated from Demarara in America with Mr. Hekker, who bought her there as a slave, in public auction. His Honour refused her to be inducted in the Christian faith, and when the Church Council of the Remonstrant Reformed Church found out about this, it assisted her in this, finding her to be a Religious and honest soul, too noble to live in an un-Christian state of slavery any longer. Oh, could her miserable fellow-sufferers enjoy freedom with her, and the Christians be less Barbarians, and Slaves!"The text tells us a lot about the young lady's identity, background, and the process that led to her baptism.

The most striking element in the report is the detailed information about Maria Zara Johanna's African background. She recalls her birthplace and its approximate location, the names of her father and mother, and her approximate age. It is therefore probable that she was enslaved in her teens or as a young adult. Unfortunately, the African names are phonetically spelled in such a way that it becomes quite hard to identify them properly. Location of birthplace and some elements in the personal names seem to indicate an origin in the Akan cultural and political area of today's Ghana. Her father's first name, Kajo, could well read as the Akan first name Kwadwo (also Kojo, or Kodjo), for Monday-born. The other names could also well be Akan in origin.

Equally interesting is the story of her arrival in the Netherlands: she was enslaved in Ghana and sent to the then Dutch plantation colony of Demarara (now Guyana), where she was bought in auction by a Mr. Hekker, presumably a plantation owner. He took her to the Netherlands, where, according to the report, she remained in slavery, until the Remonstrant Reformed Church took pity on her and brought her into the Christian fold. Not mentioned is how this helped her to gain her freedom from Mr. Hekker. Possibly the church council records may hold a key here.

Further research and invitation to assist

This blog limits itself to the registration of the etching and the identification of Maria Zara Johanna. It is likely that additional research can bring forth a lot more information about her life history. A quick search online gives her death record, for instance:Maria Sara Johanna Kajo Sanchonia, died The Hague 26 October 1834, 68 years old, born in Demarara, no further information.Only the index to this record is digitally available, so perhaps the original has more information. Writing from Ghana I do not have access to this currently.

The age given at baptism and her age at death put her birth year at circa 1766/1770. At death she apparently used a form of her father's first names as her surname. The baptism record gives no surname. However, the 21st-century index maker listed her surname as Niabi, also a name given to her father.

So far nothing further is known about Maria Zara Johanna's life, or that of her former owner. Contributions to that effect are most welcome and will be included in a follow-up to this blog. In the meantime a note has been sent to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to amend the description of the etching and identify the characters mentioned in the baptism record.

References

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Rijksstudio, Doop van een Afrikaanse vrouw in Delft, 1794, Anonymous, 1794, etching, h 183mm × w 267mm.

- Baptism register Remonstrant Reformed Church (Oude Delft), Delft, 4 July 1674 - 16 April 1809, entry 24 September 1794, scan 70.

- Death record, Civil Registry The Hague 1834, registration 28 October 1834, doc. no. 1162.

Update 27 August 2016: Death record

George Homs was so kind to provide a copy of the death certificate of Maria Zara Johanna. It confirms the information from the index quoted above, and has some added information as well.The death of Maria Sara Johanna Kajo Sanchonia is registered by Hendrik de Nijs, 65 years old, death announcer ('bidder'), and Hendrik Zoomerveldt, 50 years old, cobbler or shoemaker, both living in The Hague. De Nijs was a professional, while Zoomerveldt could be a friend or neighbour, but also a passer-by. The two listed the address where Maria Sara Johanna's died as Quarter W3 ('Wijk W3') in The Hague, which may also have been her residential address, and that she was without occupation.

The next stop will be the Municipal Archives in The Hague (Haags Gemeentearchief) to see if anything can be found about her there in non-digitised records.

|

Friday, 15 July 2016

Elmina in 1865: New photographs discovered

Pictures of Elmina

Photographs of the town of Elmina in the Dutch period, i.e before 1872, are quite rare. There are some, and there are depictions of the town in the form of drawings and lithographs, but on the whole, one does not find many clear pictures.You can imagine my surprise and elation therefore, when my colleague and friend, and comrade in arms in the Dutch history of Elmina, Natalie Everts, pointed me towards a fantastic find this morning.

The website of Mystic Seaport: The museum of America and the sea harbours a large collection of historical photographs, mainly of ships. However, hidden in the long list of ships called "Elmina", there are three photographs of the Ghanaian town of Elmina. They were taken by a man called John F. Brooks, whom I believe to be one of the American ship's captains that frequented Elmina, dated circa 1865, and made in the photographic technique called ambrotype.

With this firm date of 1865 attached to them, these images of Elmina are among the oldest surviving photographic townscapes on record.

I have ordered high resolution scans of the images, but found this discovery too important to let it wait. So here are the low resolution small-sized reproductions as they can be found on the Mystic Seaport website, with a brief description of what we see.

When the high resolutions scans become available, I will return here with a more complete description and analysis.

View from St. Jago Hill

The first two pictures, identical or almost identical, show a familiar sight: the Castle of St. George d'Elmina taken from Fort Coenraadsburg on St. Jago Hill opposite. The castle flies the Dutch flag from a very tall mast, and stands out brightly whitewashed. In addition to the castle we see the roadstead with three merchant ships, the Benya Lagoon with bridge, a part of the old town of Elmina with stone houses, all destroyed by the British in 1873, and part of Liverpool Street to the left and centre, with the row of new, flat-roofed, luxurious merchant's houses dating from the 1840s.What is special here is that the photograph shows, more than any other known picture, a fair part of the old town of Elmina.

These images link here.

| |||

| Reference: Mystic Seaport Image ID m024429 |

|

| Reference: Mystic Seaport Image ID m024429-01 |

View of High Street

The second picture is a view of what is now called the High Street in Elmina, from an elevated point, overlooking the bay on the left, with a clear view of the castle, and with Fort Coenraadsburg on St. Jago Hill dominating the right-hand side of the picture. We see the white houses in Liverpool Street in the middle, as well as some other buildings. And below the vantage point we see the street, not much more than a sandy path, some mottle and swish houses, a larger building on the opposite side of the street which seems under construction, and a walled yard of some sort in the middle, right below where the photographer stood.Although this needs more research, my first guess would be that the photographer stood inside the house known as Mount Pleasant, built by the Elmina merchant Carel Bartels in the early 1850s.

This image links here.

|

| Reference: Mystic Seaport Image ID m024428 |

Addendum

A thorough search of the Mystic Seaport database brought to light one other image from the Gold Coast, namely of the British fort at Dixcove, dated 1862. The entry has no image attached to it. Th picture is also an Ambrotype by John F. Brooks, which may mean that the date for the Elmina pictures has to be pushed back three years too, to 1862.See the link here.

Wednesday, 16 March 2016

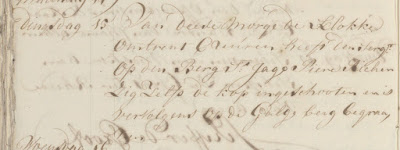

'The White Man's Grave': A suicide in Elmina, 1749 (2)

'Tuesday 15 [April 1749] This morning around 6 o'clock, the sergeant on the Hill of St. Jago, Pierre Richer, has shot himself in the head, and was subsequently buried on Gallow's Hill.'Considering that suicide was a crime, the thought occurred that there might have been a (posthumous) murder inquiry and criminal court case in the court of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea. And indeed, fiscal (read: public prosecutor) Huibert van Rijk made a case that went to court.

|

| Page 1 of the sentence on Pierre Richer |

The evidence first of all showed that:

'[...] Pierre Richer of Paris, while stationed as sergeant in Fort Coenraadsburg, had dared to take his own life with a musket, on the 15th of April 1749, around 6 o'clock in the morning [...]'So the facts of the suicide were clear. But how about the reason? The sentence report continued:

'[...] without [anybody] so far having been able to detect the reason for this enormous fact.'This uncertainty could call into question whether Pierre Richer's death was indeed a suicide? Could it not be that he had been cleaning his musket and accidentally fired it, killing himself? This question is not asked by the court, nor is there any reference made to the witness statements that may shed some light on possible circumstantial evidence pointing towards or explaining suicide.

The court had no doubts. It is considered a case of suicide, and therefore,

'the cadaver of the delinquent was, according to custom, clandestinely buried under the gallows, having perpetrated the crime of suicide and the crime of desertion, as far as it concerns his oath-bound position, as an officer on an important post.'So, in the eyes of the prosecutor and the court, Richer had not only committed the crime of murder, but by killing himself he also deserted his post as sergeant on active duty. And this, the court decided was a dangerous affair:

'All these [suicide and desertion] are matters that make for such dangerous examples in the depopulated remote domains of the State, with regard to the other few militiamen, and the harshest punishment is not even enough as a deterrent.'Sentence was passed, and Pierre Richer, deceased, was punished with the 'forfeiture and seizure' of his complete estate insofar it was within the jurisdiction of the West India Company, including his clothes, salary, allowances, et cetera.

Whether this 'punishment' was really a deterrent for others to follow Richer's example is doubtful, I would think. And moreover, the instances of suicide among Europeans were rare in any case. The court, however, had done its duty, in the name of the the Honourable Gentlemen the States General of the United Netherlands, and the Chartered West India Company.

For the full text of the sentence (in Dutch):

Sentence in the case of the suicide of Pierre Richer (PDF)

Sources:

National Archives of the Netherlands, Archives of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea (access no. 1.05.14), inv. no. 110, Elmina journal and correspondence with the outer forts, 1749, journal entry 15 April 1749 (Scan 769).

Ditto, inv. no. 9, Minutes of the meetings of the director-general and Council, 1742-1758, p. 289-290 (Scan 319 and 320)

Saturday, 5 March 2016

'The White Man's Grave': A suicide in Elmina, 1749 (1)

In any case, before the advent of modern medicine and principals of hygiene in the latter part of the nineteenth century, mortality and morbidity were high. For any arriving European it was a matter of surviving the first year and subsequently keeping a keen eye on a style of living that was as healthy as possible. And in some cases, personal physique and genetic make-up assisted survival as well.

But this is about physical health. What about psychological health? Living in West Africa was not easy on the mind either. However, this is a subject much less studied. For the Dutch presence on the Gold Coast we have one clearly documented case, that of the Asante Prince Kwamena Poku in 1850 (Doortmont & Smit, 2007: 268). He was brought to the Netherlands in 1837, with his cousin Kwasi Boakye, who went on to become a planter in the Netherlands East Indies. Kwamena Poku, a potential heir to the Asante throne, returned to the Gold Coast where he stayed at Elmina as guest of the governor. He was shunned by his uncle, the king of Asante and dissuaded from returning to Kumase, however, and subsequently found live unbearable. After lunch on 22 February 1850 he returned to his room, took a gun, and blew his brains out.

This is a case of an African gentleman returning to his own country and experiencing a severe inverse culture shock, together with utter social abandonment by his family. For Europeans, documented examples of suicide are scarce.

The Elmina Journal for 1749 mentions a suicide by a European sergeant named as Pierre Richer:

'Tuesday 15 [April 1749] This morning around 6 o'clock, the sergeant on the Hill of St. Jago, Pierre Richer, has shot himself in the head, and was subsequently buried on Gallow's Hill.'The director-general, who wrote the journal, made short shrift of the occurrence. Suicide was a crime, and hence the hurried burial on Gallow's Hill, the burial place for convicted criminals. Nothing about the possible reasons for the suicide, the poor man's state of mind in the days and weeks before he killed himself, or anything else. It happened, he was buried, and that was the end of it.

Now, some 267 years later, Pierre Richer, just another anonymous West India Company servant, becomes the first known example of a European suicide in Elmina.

Literature:

Doortmont, Michel R. & Jinna Smit, Sources for the mutual history of Ghana and the Netherlands: An annotated guide to the Dutch archives relating to Ghana and West Africa in the Nationaal Archief, 1593-1960 (Leiden / Boston: Brill 2007), p. 268.

Sources:

National Archives of the Netherlands, Archives of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea (access no. 1.05.14), inv. no. 110, Elmina journal and correspondence with the outer forts, 1749, journal entry 15 April 1749 (Scan 769).

Ditto, inv. no 367, Journal 1849-1855, journal entry 22 February 1850 (Scan 45)

Wednesday, 17 February 2016

Famine on the Gold Coast, 1749

Severe drought and crop failure are normally not connected to Ghana as a matter of course, but rather as an exception. In living memory, the year 1983 stands out, when the results of drought and crop failure early in the year were exacerbated by the influx of over 1.5 million Ghanaians flowing into the country from Nigeria, which had expelled them (Editorial Staff, '1983 A Year Ghana Would Prefer to Forget', African Globe 22 Jan 2013).

Historically, information about famine in Ghana is sparse, although sources reporting on them are available, as it turned out, when I scanned the archives of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea. This collection is in the National Archives in The Hague, but was recently also made available as high definition scans in an online repository (Archief Nederlandse Bezittingen ter Kuste van Guinea).

The particular record series I studied were the letters of the Dutch director-general (governor) at Elmina to his superiors in the Netherlands, reporting on important affairs. In his letter of 15 July 1749, director-general Jan van Voorst wrote about the dire state of the Dutch possessions, highlighting the lack of personnel and provisions, and the poor condition of trade with the hinterland. As usual in this period, he referred to warfare and the blockade of trade routes as an important reason. However, near the end of his letter, almost as an afterthought, Van Voorst pointed at another serious reason for the poor state of affairs:

'[...] Also, in the last six months [i.e. since January 1749], such a sad and serious famine visited the whole Coast (caused by an extraordinary drought in the past year, which made the cereal crops fail), that many natives died daily from hunger. Had I not had some victuals in store during that time, and having had the opportunity to buy some for the maintenance of the garrison, truly, [Your Honourable Gentlemen], the fate of the white people would have been miserable, because the natives would not sell provisions for gold, and thus the transportation of victuals [to the Gold Coast from the Netherlands] is highly necessary.'

In summary: 1748 had seen a serious drought on the Gold Coast, in which the crops had failed; cereals are mentioned, but most likely vegetables and other food-crops were affected too, not to mention livestock. In the following dry season of 1748-1749, this led to severe shortages in food supply, and eventually to a famine that affected large parts of the population, including those (the Europeans mainly) that could secure access to imported foodstuffs. 'Many' - dozens, maybe hundreds of - people died on a daily basis. And we have to keep in mind here that the figures are those Van Voorst registered from his immediate surroundings, so one can hazard to guess what the situation in the hinterland of the coastal settlements was like.

Thus, a social economic disaster visited the Gold Coast in that year, most likely with immediate geo-political consequences, as well as a fall out of several years to come.

It is just a note in a letter, easily missed. However, a source of importance for our knowledge of the social-economic and political history of Ghana, and – in terms of methodology – a pointer to a source that may yield more information on the subject.

Addition (15 March 2016):

Further scrutiny of the Elmina journals brought to light an entry by director-general Van Voorst on 11 September 1748, in which he warns the captain of the Dutch West India Company slave trading ship De Maria Galeij, that he has to take into account that he cannot get any fresh drinking water at Elmina, 'because of the excessive drought, [which continues] since some time.' This confirms that the rainy season of 1748 was extremely dry. All ships are sent to the port of Shama, on the estuary of the River Prah, to take in fresh water.

Sources:

National Archives of the Netherlands, Archives of the Dutch Possessions on the Coast of Guinea (acc. no. 1.05.14), inv. no. 265, Letters to the directors of the Dutch West India Company, doc. no.: letter by director-general Jan van Voorst, Elmina 15 July 1749 (link).

National Archives of the Netherlands, Archives of the Dutch Possessions on the Coast of Guinea (acc. no. 1.05.14), inv. no. 109, Elmina Journal and correspondence with the outer forts, 1748, Journal entry 11 September 1748, with letter by director-general Jan van Voorst to captain Herloff of the W.I.C. ship De Maria Galeij in the roadstead of Elmina (link).

References:

Editorial Staff, '1983 A Year Ghana Would Prefer to Forget', African Globe 22 Jan 2013.

'El Nino threatens "millions in east and southern Africa"', BBC World News Africa website, 15 November 2015.

See also:

Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World (London: Verso Books 2001).

Late Victorian Holocausts. (2016, February 14). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11:39, February 17, 2016.