'Tuesday 15 [April 1749] This morning around 6 o'clock, the sergeant on the Hill of St. Jago, Pierre Richer, has shot himself in the head, and was subsequently buried on Gallow's Hill.'Considering that suicide was a crime, the thought occurred that there might have been a (posthumous) murder inquiry and criminal court case in the court of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea. And indeed, fiscal (read: public prosecutor) Huibert van Rijk made a case that went to court.

|

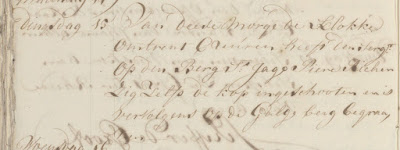

| Page 1 of the sentence on Pierre Richer |

The evidence first of all showed that:

'[...] Pierre Richer of Paris, while stationed as sergeant in Fort Coenraadsburg, had dared to take his own life with a musket, on the 15th of April 1749, around 6 o'clock in the morning [...]'So the facts of the suicide were clear. But how about the reason? The sentence report continued:

'[...] without [anybody] so far having been able to detect the reason for this enormous fact.'This uncertainty could call into question whether Pierre Richer's death was indeed a suicide? Could it not be that he had been cleaning his musket and accidentally fired it, killing himself? This question is not asked by the court, nor is there any reference made to the witness statements that may shed some light on possible circumstantial evidence pointing towards or explaining suicide.

The court had no doubts. It is considered a case of suicide, and therefore,

'the cadaver of the delinquent was, according to custom, clandestinely buried under the gallows, having perpetrated the crime of suicide and the crime of desertion, as far as it concerns his oath-bound position, as an officer on an important post.'So, in the eyes of the prosecutor and the court, Richer had not only committed the crime of murder, but by killing himself he also deserted his post as sergeant on active duty. And this, the court decided was a dangerous affair:

'All these [suicide and desertion] are matters that make for such dangerous examples in the depopulated remote domains of the State, with regard to the other few militiamen, and the harshest punishment is not even enough as a deterrent.'Sentence was passed, and Pierre Richer, deceased, was punished with the 'forfeiture and seizure' of his complete estate insofar it was within the jurisdiction of the West India Company, including his clothes, salary, allowances, et cetera.

Whether this 'punishment' was really a deterrent for others to follow Richer's example is doubtful, I would think. And moreover, the instances of suicide among Europeans were rare in any case. The court, however, had done its duty, in the name of the the Honourable Gentlemen the States General of the United Netherlands, and the Chartered West India Company.

For the full text of the sentence (in Dutch):

Sentence in the case of the suicide of Pierre Richer (PDF)

Sources:

National Archives of the Netherlands, Archives of the Netherlands Possessions on the Coast of Guinea (access no. 1.05.14), inv. no. 110, Elmina journal and correspondence with the outer forts, 1749, journal entry 15 April 1749 (Scan 769).

Ditto, inv. no. 9, Minutes of the meetings of the director-general and Council, 1742-1758, p. 289-290 (Scan 319 and 320)