"Baptism of a negro lady from the Coast of Africa"

In the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, there is an image of a baptism ceremony of a 'negro lady from the Coast of Africa.' The caption further reads that the ceremony took place in the Remonstrant Reformed church of Delft on 24 September 1794. In pen is added that the ceremony was performed by the Rev. Pieter van der Meersch, and that the the ceremony was set to Ephesians 5 verse 8: "For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Live as children of light." On the pulpit a reference is made to Psalm 36, but it is unclear if this has bearing on the ceremony.The image is detailed, with the African lady kneeling, the minister performing the baptism and a man and a woman assisting. A considerable congregation is looking on. However, except for the name of the minister, nobody is mentioned by name. Apparently the maker of the print and caption was more interested in the rarity value of the occasion - an African lady being baptised - than in the human aspect of it, in terms of a social occasion.

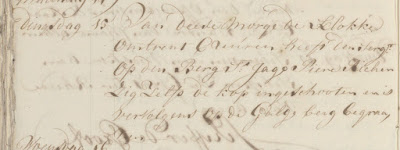

As the date and location of the baptism are mentioned in the caption, it is possible to look up the original registration of in the records of the Remonstrant Reformed Church of Delft. As it happens these have been digitised and can be found here.

"An African young daughter [...] named Maria Zara Johanna"

The registration is very elaborate and runs as follows:"The 24th of September on Wednesday night was baptised in this church, by Rev. A. van der Meersch, an African young daughter, who was named at Holy Baptism Maria Zara Johanna. As witnesses stood the overseer Johannes Guus, and Ms. Zara Turfkloot, wife of Rev. Van der Meersch, who also led her to Holy Baptism. According to her own information she was born in Zoogwoin, on the Coast of Guinea, a day's travel from St. Elmina [sic], and probably circa 24 years old. Her father's name is Cajo Sainquo Niabi, and her mother's name is Masa Oribo. She was repatriated from Demarara in America with Mr. Hekker, who bought her there as a slave, in public auction. His Honour refused her to be inducted in the Christian faith, and when the Church Council of the Remonstrant Reformed Church found out about this, it assisted her in this, finding her to be a Religious and honest soul, too noble to live in an un-Christian state of slavery any longer. Oh, could her miserable fellow-sufferers enjoy freedom with her, and the Christians be less Barbarians, and Slaves!"The text tells us a lot about the young lady's identity, background, and the process that led to her baptism.

The most striking element in the report is the detailed information about Maria Zara Johanna's African background. She recalls her birthplace and its approximate location, the names of her father and mother, and her approximate age. It is therefore probable that she was enslaved in her teens or as a young adult. Unfortunately, the African names are phonetically spelled in such a way that it becomes quite hard to identify them properly. Location of birthplace and some elements in the personal names seem to indicate an origin in the Akan cultural and political area of today's Ghana. Her father's first name, Kajo, could well read as the Akan first name Kwadwo (also Kojo, or Kodjo), for Monday-born. The other names could also well be Akan in origin.

Equally interesting is the story of her arrival in the Netherlands: she was enslaved in Ghana and sent to the then Dutch plantation colony of Demarara (now Guyana), where she was bought in auction by a Mr. Hekker, presumably a plantation owner. He took her to the Netherlands, where, according to the report, she remained in slavery, until the Remonstrant Reformed Church took pity on her and brought her into the Christian fold. Not mentioned is how this helped her to gain her freedom from Mr. Hekker. Possibly the church council records may hold a key here.

Further research and invitation to assist

This blog limits itself to the registration of the etching and the identification of Maria Zara Johanna. It is likely that additional research can bring forth a lot more information about her life history. A quick search online gives her death record, for instance:Maria Sara Johanna Kajo Sanchonia, died The Hague 26 October 1834, 68 years old, born in Demarara, no further information.Only the index to this record is digitally available, so perhaps the original has more information. Writing from Ghana I do not have access to this currently.

The age given at baptism and her age at death put her birth year at circa 1766/1770. At death she apparently used a form of her father's first names as her surname. The baptism record gives no surname. However, the 21st-century index maker listed her surname as Niabi, also a name given to her father.

So far nothing further is known about Maria Zara Johanna's life, or that of her former owner. Contributions to that effect are most welcome and will be included in a follow-up to this blog. In the meantime a note has been sent to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to amend the description of the etching and identify the characters mentioned in the baptism record.

References

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Rijksstudio, Doop van een Afrikaanse vrouw in Delft, 1794, Anonymous, 1794, etching, h 183mm × w 267mm.

- Baptism register Remonstrant Reformed Church (Oude Delft), Delft, 4 July 1674 - 16 April 1809, entry 24 September 1794, scan 70.

- Death record, Civil Registry The Hague 1834, registration 28 October 1834, doc. no. 1162.

Update 27 August 2016: Death record

George Homs was so kind to provide a copy of the death certificate of Maria Zara Johanna. It confirms the information from the index quoted above, and has some added information as well.The death of Maria Sara Johanna Kajo Sanchonia is registered by Hendrik de Nijs, 65 years old, death announcer ('bidder'), and Hendrik Zoomerveldt, 50 years old, cobbler or shoemaker, both living in The Hague. De Nijs was a professional, while Zoomerveldt could be a friend or neighbour, but also a passer-by. The two listed the address where Maria Sara Johanna's died as Quarter W3 ('Wijk W3') in The Hague, which may also have been her residential address, and that she was without occupation.

The next stop will be the Municipal Archives in The Hague (Haags Gemeentearchief) to see if anything can be found about her there in non-digitised records.

|